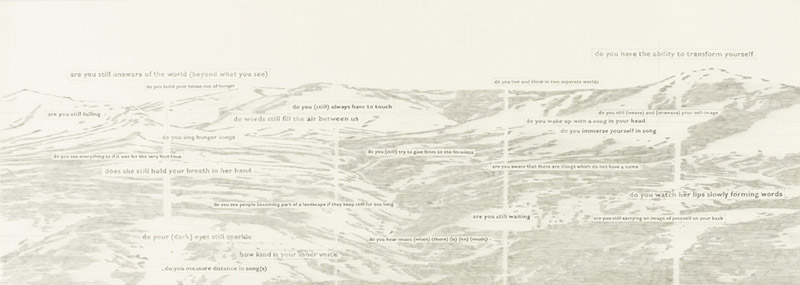

| Nanda van Bodegraven This image remained with me for months after seeing it at the KunstRai. Seen from distance it is a landscape. When I get closer, I see the questions. After reading some of the questions I discover that it is an inner landscape. Fascinated, I keep looking. Reading. I sense a great longing in the questions. For someone? For the past? Or for an optimistic future in which the past plays no role? The longer I look, the more I become the ‘you’ of the questions. I am startled when I realise how much it speaks to me. I enter into a conversation with myself. Some questions captivate me for a long time. It is as if I am walking through the mountains and valleys myself. Walking sometimes from one question to another and then back again. Some questions have no meaning, even after I have walked past them for the sixth time. Others become louder and clearer and more meaningful. I want to answer some questions. Or if I can’t manage to, I want to examine what it is exactly that I identify with in the question. Someone else, a young woman, comes and stands next to me. I make room for her. She looks with me. Does she see what I see? Is she walking as I am? I follow her eyes. With the woman next to me I am struck even more by the intimacy of the image. And it is hanging there, just like that, out in the open. Like a meeting place, like a conversation. |

Dit beeld bleef mij maanden bij toen ik

het zag op de Kunst Rai. Vanuit de verte is het een landschap. Als

ik dichterbij kom, zie ik de vragen. Na lezen van wat vragen ontdek

in dat het een innerlijk landschap is. Nanda van Bodegraven |

| from: Come for a Walk in an Inner Landscape

/ Wandel mee in een innerlijk landschap Nieuwe Stemmen. 2008 image: Are You Still Unaware Of The World (Beyond What You See). from (Seen From Above). 2007. pencil / paper. 50 x 140 cm. photo: P.Cox. private collection |

Arno Kramer 2007 Simon Benson’s work covers a large area; from installations, in which three dimensional works are combined with drawings, to presentations of just his drawings. His is, as it happens, not just a very gifted and precise draughtsman of subjects like architecture, nature and the human figure in various forms, portraits for example, but he also manages to combine these subjects with text in a distinctive way. The use of text in works, that is strongly

visual and is itself visual art, is no longer anything new. The

use of actual legible text in a work of art irrevocably sets the

observer thinking. Do you look for references to literature, to

philosophy or to the visual arts, or is the work intrinsically a

mix of all these things? You have the idea, really, that the artist

is revealing a lot of himself. That he attains a degree of perfection

in his drawings is all well and good, but this never just leads

to a show of skill. You are drawn into an intellectual world which

you, to some extent, want to fathom; but at the very moment you

think you are getting close to understanding its meaning, partly

through the lines of text, Its possible lose yourself in the quality

of images in another wonderful part of the drawing. In some drawings,

especially where the head that is the subject, layers of images

are drawn on top of each other. In this way a sort of alienation

arises, but the sampled images form at the same time metaphors for

thoughts and feelings.Benson doesn’t

use text in all his drawings. When he does the text is never used

in the dynamic of the drawing decoratively or as an impulsive filling

in. They are self-written statements or lines of poetry, which because

of their prominence are unable to conceal their content. |

| Simon Benson’s werk bestrijkt een groot

gebied, van installaties, waarin soms ruimtelijk werken met tekeningen

worden gecombineerd, tot presentatie van zijn tekeningen alleen. Hij

is overigens niet alleen een zeer begenadigd en precieze tekenaar

van onderwerpen als architectuur, natuur, de mens in veel hoedanigheden,

portretten, enzovoort, hij ziet ook kans om deze onderwerpen op bijzondere

wijze met tekst te verbinden. Tekst gebruiken in werk, dat toch zeer visueel is en tot de beeldende kunst behoort, is geen nieuwigheid meer. Het gebruikmaken van feitelijke leesbare tekst in een kunstwerk zet de kijker onherroepelijk aan het denken. Zoek je referenties in de literatuur, in de filosofie of de beeldende kunst of is het werk inhoudelijk een mix van dit alles? Het werk van Simon Benson wekt soms de indruk beredeneert en filosofisch te zijn. Dat is wellicht op het niveau van die taal zo, maar als je zijn tekeningen op het materiële en technische bekijkt, zijn ze uiterst subtiel, speels en sensibel. Zijn werk is meestal zonder kleur. Qua onderwerpen lijkt niets onmogelijk. Personen, portretten, bomen, stadsgezichten alles kan. Dikwijls worden onderwerpen ook nog weer gecombineerd zonder dat je de indruk krijgt dat er geen controle over het beeld is. Je hebt echt het idee dat er veel van de geest van de kunstenaar wordt geopenbaard. Dat hij in die getekende onderwerpen bovendien een mate van perfectie bereikt is mooi, maar het leidt nooit tot alleen maar staaltjes vaardigheid. Je duikt in een geestelijke wereld die je ook deels wilt doorgronden, maar op het moment dat je denkt iets op het “spoor” te zijn aan betekenis, mede door de regels tekst, kun je door een ander prachtig deel in de tekening weer alleen in de beeldende kwaliteit wegdwalen. In sommige tekeningen, vooral als het hoofd het onderwerp vormt, zijn er lagen van beelden door elkaar getekend. Op die manier ontstaat vervreemding, maar vormen die gesamplede beelden eveneens metaforen voor gedachtegoed en gevoelens. Niet in alle tekeningen gebruikt Benson tekst. Als hij dat doet is die tekst ook nooit in de dynamiek van het tekenen opgenomen, als decoratie of als impulsieve beeldvullende toevoeging. Het zijn zelf geschreven bewuste statements of regels poëzie, die zich door die prominente aanwezigheid in hun inhoud ook niet “verschuilen”. Simon Benson gebruikt in zijn werk meestal zijn moedertaal, met soms uitwijkingen naar het Duits, Frans of Italiaans. Je wordt door die uitgedachte typografie ook gedwongen om die teksten te lezen. De samenhang met het beeld is soms streng, soms speels. Maar altijd bijzonder. |

| Arno Kramer 2007 |

| Mirjam de Winter, PHOEBUS Rotterdam. 2004 |

| Simon Benson is a draughtsman

above all else. In pencil, on A4 and A3 size paper, you find almost

everything: from almost invisible organic lines drawn in a searching

automatic hand, to harder lines, drawn with the help of a ruler or

a template; as well as areas of solid fill or cross-hatched and soft

nebulous planes. Since the end of the 80’s nature and architecture

have been his main subjects in which he can deploy his drawing skills.

In the course of the 90’s, language and text make an appearance,

along with the human form, sensory perception and feelings. In 1998,

he makes the first self-portraits. In the meantime, new techniques

are being used in the works on paper: photography and digital prints.

Alongside all this, Benson has been making wall-paintings and three

dimensional wall and floor objects made from mdf: he has also realised

a number of public space commissions. In 1997, Simon Benson, made a text-piece, ‘Universal Anatomy’, in the form of a digital and a silk-screen print. It consists of a list of about 300 Italian words. (Italy referring to the beginnings of art in the Renaissance). The scope of this theme becomes clear: from roof to foundation, mountain peak to valley floor, from human head to feet – the body expanded to include perception, feeling and thought – all this subject matter described in one descending movement. At the same time, with a fascination for crossovers, Simon Benson drew a house in the form of a head, or a tree that appeared to be speaking; and he also made an installation entitled ‘An Anthropomorphic Landscape’, with consisted of a series of mdf objects with an block-like architectural appearance, which contained textual references to certain facets of the human form. Not just in this conceptual framework -that

to this day continues to grow and is still a way to get to know

Simon Benson’s work- but individual text works also play a

role. For example, ‘Solutio’, ‘Heiliger Platz’,

Senza Fiato’, ‘Fluchtpunkt’, ‘Seed’,

‘Cielo’ and others confront you with a greater or lesser

degree of That Simon Benson is inspired, on

various levels, by the traditions of western art and architecture

is discernable in his work. Sometimes it is possible to point out

variations on existing images, like in the references to Dürer’s

drawings or Botticelli’s, or in the assimilation of architectural

drawings of Gothic cathedrals or Le Corbusier’s buildings.

As far as sources from literature are concerned, Simon Benson made,

in 1999, a series of drawings based on Dante’s Divine Comedy

and lately he has been inspired by James Joyce's 'Ulysses', especially

by the notion of a varyingly, inward and outward looking subjectivity.

‘Thought Through My Eyes’- eyes open and closed. His

work is becoming more and more personal. Image and text, increasingly

woven together – something like what you see in a present

day source of his: television and computer culture. |

| Simon Benson is vooral een tekenaar.

In potlood op papier, op de formaten A4 en A3, is bijna alles er:

van organische lijnen, die bijna onzichtbaar in een zoekend of automatisch

handschrift zijn neergezet tot hardere, langs een liniaal of schabloon

getrokken lijnen; zowel egale als gearceerde en wolkachtige getekende

vlakken. Vanaf het eind van de jaren '80 zijn natuur en architectuur

de omvattende onderwerpen, waarin hij zijn tekenkundige kwaliteiten

kan neerleggen. In de loop van de jaren '90, doen taal en tekst hun

intrede, evenals het menselijk lichaam, zintuiglijke waarnemingen

en gevoelens. Vanaf 1998 verschijnen zelfportretten. Inmiddels zijn

er dan nieuwe technieken in de tweedimensionale papierwerken gebruikt:

fotografie en digitale prints. Er zijn daarnaast wandschilderingen

en drie-dimensionale wand- en vloerobjecten in mdf ontstaan; en er

zijn opdrachten in de openbare ruimte gerealiseerd. In 1997 maakte Simon Benson een tekstwerk, 'Universal Anatomy', in de vorm van een digitale print en een zeefdruk, bestaande uit een lijst van ca. driehonderd Italiaanse begrippen (Italië als referentie aan een van de beginmoment envandekunstderenaissance. De reikwijdte van de thematiek wordt duidelijk: van toren tot fundament, van bergtop tot voet van de berg, van menselijk hoofd tot tenen - het lichaam nog met uitdijingen naar waarneming, voelen en denken - al deze onderwerpen worden in één beweging van boven naar beneden toe met woorden afgetast. In een fascinatie voor cross-overs tekent Simon Benson in dezelfde tijd een huis om een menselijk hoofd, of een boom die taal lijkt te spreken; en hij maakt een installatie, getiteld 'Anthropomorphic Landscape', bestaande uit mdf-sculpturen die er blokmatig, architecturaal uitzien, maar die tevens benamingen van menselijke lichaamsdelen bevatten. Niet alleen dit begrippenkader als geheel - dat tot op de dag van vandaag groeiende is en nog altijd een aanknopingspunt vormt om nader kennis te maken met het werk van Simon Benson - maar ook afzonderlijke begrippen spelen een rol. Bijvoorbeeld 'Solutio', 'Heiliger Platz', 'Senza Fiato' (ademloos, zonder adem), 'Fluchtpunkt', 'Seed', 'Cielo' en andere begrippen confronteren de toeschouwer met hun meer of mindere mate van dubbelzinnigheid, hun under- of overstatement - en bieden zo ruimte voor associatie. Woorden of letters zijn soms door een heldere, maar abstracte rangschikking in eerste instantie onleesbaar. Bijvoorbeeld de zestien letters van de naam van galerie ' P H O E B U S R O T T E R D A M ' zijn in een raster van vier maal vier letters op de gevel van het pand aangebracht. De tekst dan aanknopingspunt én geheimtaal, een labyrint om in te vertoeven, een punt om bij stil te staan, te dromen of verder te denken. Dat Simon Benson op veel niveaus geïnspireerd is door de traditie van de westerse beeldende kunst en architectuur en de wereldliteratuur is voelbaar in zijn werk. Soms zijn variaties op bestaand beeldmateriaal ook aanwijsbaar, zoals in de beeldcitaten van tekeningen van Dürer en Botticelli en in het verwerken van architectuurtekeningen van gotische kathedralen en van gebouwen ontworpen door Le Corbusier. Wat literaire bronnen betreft heeft Simon Benson in 1999 een serie tekeningen gemaakt naar Dante's 'Divinia Commedia' en is hij de laatste jaren onder meer geinspireerd door James Joyce's 'Ulysses', met name door de gedachte van het subjectieve, afwisselend naar binnen en naar buiten gericht zijn: 'Thought through My Eyes' - de ogen zijn geopend en gesloten. Het werk wordt steeds persoonlijker. Beeld en tekst zijn daarbij meer en meer verweven - zoals in de hedendaagse bron van het werk: de televisie- en computercultuur. |

| Mirjam de Winter, PHOEBUS Rotterdam. 2004 |

CANIS ZIJLMANS from Garden of Earthly Delights, 21 interpretations in 8 Rotterdamse gallerys, 2001 Hieronymus Bosch didn’t just reflect his physical everyday surroundings, but with The Garden of Earthly Delights he tried to represent ‘the all-embracing system’ of life complete with all facets of lust and desire. Dealt with schematically are the creation, the triumphal procession on earth and the end with the inevitable reckoning of sinners. Artist Simon Benson is no stranger to Hieronymus Bosch’s fantastical imagery. A root grows out of a slender back representing the uprootedness of the figure. A house built around a head depicts the house of thought and at the same time the isolation of the bearer. The vain creature of another drawing carries as punishment a mountain on its head to bend it downwards. In a similar way to in the Purgatorio from Dante Alighieri's classic poem The Divine Comedy from the 13th century. For his objects and drawings Benson draws much inspiration from literature. He uses words from different languages as form and content. In 1995 he added his Universal Anatomy to his conceptual framework. A continually growing list of words placed in such an order that they form a sort of explorative description of parts of the body, of a building and elements of a landscape. The Egyptians kept the organs of the dead,

separate from the mummies, in pots. The deceased made the journey

into the afterlife split up in parts. Benson inscribes pots, which

bring to mind Egyptian canoptic jars, with evocative words such

as ‘shadow’, ‘hunger’, ‘pain’

and ‘dream’. “As far as the meaning of Hieronymus

Bosch’s work is concerned,” says Benson, “a lot

of interpretations are possible. I believe his works can never be

completely understood, because it is just not possible to look through

the eyes of someone from the late middle-ages.” At Phoebus Rotterdam Benson is showing,

among other things, an installation made up of drawings of subjects

of which Bosch also made a lot of use of in the construction of

his allegoric overall picture. Language is also here: the index

of Dirk Bax’s Hieronymus Bosch - His Picture-Writing Deciphered

is the source for some drawings. |

| |

Hieronymus Bosch spiegelde niet alleen zijn fysieke leefomgeving, maar probeerde met De Tuin der Lusten 'het alles omvattende systeem' van het leven uit te beelden met alle facetten van lust en begeerte. Schematisch komen aan bod het ontstaan, de triomftocht over de aarde en het einde met de onafwendbare afrekening met de zondaars. Die namen tijdens het leven te grote happen van de appel uit de Hof van Eden. De fantastische beeldtaal van Hieronymus Bosch is beeldend kunstenaar Simon Benson (1956, London) niet vreemd. Uit een iele rug groeit een wortelstok, die de ontheemding van de personage aangeeft. Een om een hoofd gebouwd huis verbeeldt enerzijds het huis der gedachten en tegelijk de opgeslotenheid van de drager. De ijdeltuit op een andere tekening draagt als 'buigstraf' een berg op het hoofd. Net zoals het gebeurde op De Louteringsberg in Dante Alighieri's cultuurepos uit de 13 de eeuw La Divina Commedia. Voor zijn objecten en tekeningen zoekt Benson veelal inspiratie in de literatuur. Woorden uit verschillende talen gebruikt hij naar vorm en inhoud. In 1995 voegt hij met zijn Universal Anatomy aan zijn beeldende werk een begrippenkader toe. Een nog groeiende lijst van woorden zijn zo op volgorde geplaatst, dat ze delen van het lichaam, van de gebouwde omgeving en landschappelijke elementen al beschrijvend ‘aftasten’. Egyptenaren bewaarden de organen van doden los van de mummies in

potten. Opgesplitst in delen maakte de overledenen de reis naar

het hiernamaals. Benson voorziet potten, die doen denken aan Egyptische

kanopen, van evocatieve worden als 'schaduw', 'honger', 'pijn' en

'droom'. ,,Wat betreft de betekenis van het werk van Hieronymus Bosch,''

stelt Benson, ,,zijn veel interpretaties mogelijk. Naar mijn mening

kunnen zijn werken nooit helemaal worden begrepen, omdat we nu eenmaal

niet met de ogen van iemand uit de Late Middeleeuwen kijken.'' Bij Phoebus Rotterdam toont Benson onder meer een uit tekeningen

opgebouwde installatie met onderwerpen waarvan ook Bosch veelvuldig

gebruik maakte voor de opbouw van z'n allegorische totaalbeelden.

Ook de taal, hier: de index van Hieronymus Bosch - His Picture-Writing

Deciphered van Dirk Bax is bron voor sommige tekeningen. CANIS ZIJLMANS from Tuin der Lusten, 21 interpretaties in 8 Rotterdamse galeries, 2001 |